Sparse TF-IDF Example

Text analysis of Jane Austen

Source:vignettes/articles/sparse-example.Rmd

sparse-example.RmdIt is a truth universally acknowledged than an article author in possession of a Jane Austen dataset must be in want of a k-nearest neighbor graph.

In searching for a good example of working with sparse data, text analysis is a good fit. Using TF-IDF on a corpus of text documents naturally creates long sparse vectors. We shall use janeaustenr which you can see used for TF-IDF in this tidytext vignette. However due to my lack of experience with tidy data principles, I will be using tm and slam to create the TF-IDF matrix.

This article was inspired by a similar example in Python.

This is not a Vignette

As we need to install and load a lot of packages this is not a vignette and I won’t show all the output unless it’s interesting or relevant to the task at hand, but you should get similar results if you install the packages and run all the code.

Setup

Let’s install some packages:

install.packages(c(

"tm",

"slam",

"janeaustenr",

"dplyr",

"uwot",

"Matrix",

"RSpectra",

"RColorBrewer",

"ggplot2"

))And then load them:

Preprocessing the Text Data

Let’s start by getting the data. The austen_books()

function returns a tibble with the text of all of Jane Austen’s six

novels, with about 70 characters worth of text per row.

data <- austen_books()

dim(data)[1] 73422 2There is a book factor column that tells us what book

each line of text is from and then the text contains the

text itself.

head(data, 10)# A tibble: 10 × 2

text book

<chr> <fct>

1 "SENSE AND SENSIBILITY" Sense & Sensibility

2 "" Sense & Sensibility

3 "by Jane Austen" Sense & Sensibility

4 "" Sense & Sensibility

5 "(1811)" Sense & Sensibility

6 "" Sense & Sensibility

7 "" Sense & Sensibility

8 "" Sense & Sensibility

9 "" Sense & Sensibility

10 "CHAPTER 1" Sense & SensibilityOk, that’s not a lot of text in those rows and a lot of pre-amble. Let’s take a look at the end (spoiler alerts for the end of Persuasion):

tail(data, 10)# A tibble: 10 × 2

text book

<chr> <fct>

1 "affection. His profession was all that could ever make her friends" Persuasion

2 "wish that tenderness less, the dread of a future war all that could dim" Persuasion

3 "her sunshine. She gloried in being a sailor's wife, but she must pay" Persuasion

4 "the tax of quick alarm for belonging to that profession which is, if" Persuasion

5 "possible, more distinguished in its domestic virtues than in its" Persuasion

6 "national importance." Persuasion

7 "" Persuasion

8 "" Persuasion

9 "" Persuasion

10 "Finis" PersuasionAlright, so we can expect a lot of blank rows. I’d like a bit more

text per entry (and also this reduces the number of rows we need to

process during neighbor search). Let’s group the rows into chunks of 10

and then collapse them. If you want to experiment with this, then you

can change the n_chunks value below.

n_chunks <- 10

data_processed <- data |>

group_by(`book`) |>

mutate(`row_group` = ceiling(row_number() / n_chunks)) |>

group_by(`book`, `row_group`) |>

summarise(text = paste(`text`, collapse = " ")) |>

ungroup()

dim(data_processed)[1] 7344 3

head(data_processed)# A tibble: 6 × 3

book row_group text

<fct> <dbl> <chr>

1 Sense & Sensibility 1 "SENSE AND SENSIBILITY by Jane Austen (1811) CHAPTER 1"

2 Sense & Sensibility 2 " The family of Dashwood had long been settled in Sussex. Their estate was large, and their residence was at Norland Park, in t…

3 Sense & Sensibility 3 "alteration in his home; for to supply her loss, he invited and received into his house the family of his nephew Mr. Henry Dashwo…

4 Sense & Sensibility 4 " By a former marriage, Mr. Henry Dashwood had one son: by his present lady, three daughters. The son, a steady respectable youn…

5 Sense & Sensibility 5 "father only seven thousand pounds in his own disposal; for the remaining moiety of his first wife's fortune was also secured to …

6 Sense & Sensibility 6 "son's son, a child of four years old, it was secured, in such a way, as to leave to himself no power of providing for those who …Text Analysis

Next, we must make some decisions about the text pre-processing. You shouldn’t take any of my decisions as some gold standard of how to do text processing. The good news is that you can experiment with different approaches and visualizing the results with UMAP should provide some feedback.

corpus <-

Corpus(VectorSource(data_processed$text)) |>

tm_map(content_transformer(tolower)) |>

tm_map(removePunctuation) |>

tm_map(removeNumbers) |>

tm_map(removeWords, stopwords("english")) |>

tm_map(stripWhitespace)Now we can create the TF-IDF matrix:

tfidf <- weightTfIdf(DocumentTermMatrix(corpus))

dim(tfidf)[1] 7344 18853So nearly 20,000 columns. That’s a lot of dimensions. For a lot of downstream analysis with dimensionality reduction a typical workflow would involve:

- Potentially converting this to a dense representation. As we only have 7,000 rows this is not a huge memory burden. But if you decided to use the original data, you would now have a matrix 10 times the size.

- Do some linear dimensionality reduction to a more dense representation, e.g. Truncated SVD to a few hundred (at most) dimensions. Or maybe a random projection? In a lot of these cases, there are ways to do this with the sparse input so you wouldn’t necessarily need to densify the initial matrix.

Nonetheless, this involves making a decision about the number of

dimensions to keep, you need to track what sort of information loss is

involved with that decision, spend the time to do the dimensionality

reduction, and then it’s more data to keep track of. This is where

rnndescent helps by being able to generate the neighbor

graph from the sparse representation directly.

Some More Preprocessing

Just before we go only further, rnndescent only works

with dgCMatrix so we need to convert the tf-idf matrix:

tfidf_sp <-

sparseMatrix(

i = tfidf$i,

j = tfidf$j,

x = tfidf$v,

dims = dim(tfidf)

)And we should normalize the rows. Sadly, apply doesn’t

work well with sparse matrices, so we have to be a bit more creative. An

L2 normalization looks like:

I’m going to use a divergence-based distance metric which assumes that each row is a probability distribution so I will do an L1 normalization which requires even more creativity. This gist by privefl was my guide here:

l1_normalize <- function(X) {

res <- rep(0, nrow(X))

dgt <- as(X, "TsparseMatrix")

tmp <- tapply(dgt@x, dgt@i, function(x) {

sum(abs(x))

})

res[as.integer(names(tmp)) + 1] <- tmp

Diagonal(x = 1 / res) %*% X

}

tfidf_spl1 <- l1_normalize(tfidf_sp)

head(rowSums(tfidf_spl1))[1] 1 1 1 1 1 1Nearest Neighbor Search

With only 7000 rows, we can do a brute force search and get the exact nearest neighbors.

tfidfl1_js_bf <-

brute_force_knn(

tfidf_spl1,

k = 15,

metric = "jensenshannon",

n_threads = 6,

verbose = TRUE

)10:19:28 Calculating brute force k-nearest neighbors with k = 15 using 6 threads

0% 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100%

[----|----|----|----|----|----|----|----|----|----]

***************************************************

10:20:52 FinishedThis only takes just over a minute with 6 threads on my 8th-gen Intel i7 laptop which is no longer cutting-edge.

Hubness

I always strongly recommend looking at the distribution of the edges throughout the graph, and specifically looking at the hubness. First generate the k-occurrences:

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

1 6 11 15 19 167 This is telling us about the popularity of items in the dataset, i.e. while every item has 15 neighbors, which items tend to show up in the neighbor list of items more than average? If an item has a k-occurrence higher than 15 then it’s more popular than average, and vice versa. An item with a k-occurrence of 1 is called an anti-hub, and is an item that is never a neighbor of any other item (the one edge it has is to itself). Conversely, we can see that some items are very popular, with a k-occurrence more than ten times higher than average. These could definitely be considered hubs.

Here’s the k-occurrences of the top 6 most popular items:

[1] 129 137 138 152 158 167And here is how many anti-hubs we have:

sum(k_occurrences == 1)[1] 129So 129 pieces of text in the corpus are not considered to be in the top-15 neighbors of any other piece of text. Not quite 2% of the dataset.

Note that the values you get for hubness are highly dependent on things like how the dataset is scaled, what distance you use and obviously the number of neighbors. In this case, we’re doing pretty ok. Using the Euclidean distance on high-dimensional data tends to produce very large numbers of hubs, which can really distort the downstream analysis so it’s important to check this.

Hub and Hubbability

Perhaps we can learn something about the dataset by taking a closer look at the hubs and anti-hubs. The hubs represent items which are seen as similar by lots of other items, so you could imagine that these items represent the most Jane Austen-like pieces of text in the dataset. Meanwhile the anti-hubs must be less usual prose in some way. Let’s look at the popular text first.

Popular Text

popular_indices <- head(order(k_occurrences, decreasing = TRUE))

data_processed[popular_indices, c("book", "text")]# A tibble: 6 × 2

book text

<fct> <chr>

1 Mansfield Park "You will be what you ought to be to her. I hope it does not distress you very much, Fanny?\"…

2 Emma "know any body was coming. 'It is only Mrs. Cole,' said I, 'depend upon it. Nobody else would…

3 Pride & Prejudice "Jane? Shall you like to have such a brother?\" \"Very, very much. Nothing could give either…

4 Emma " \"Perhaps she might; but it is not every man's fate to marry the woman who loves him best. …

5 Northanger Abbey " \"Henry!\" she replied with a smile. \"Yes, he does dance very well.\" \"He must have thou…

6 Pride & Prejudice " \"I wish you joy. If you love Mr. Darcy half as well as I do my dear Wickham, you must be v…Here’s the full text from the most popular item:

data_processed[popular_indices[1], ]$text[1] "You will be what you ought to be to her. I hope it does not distress you very much, Fanny?\" \"Indeed it does: I cannot like it. I love this house and everything in it: I shall love nothing there. You know how uncomfortable I feel with her.\" \"I can say nothing for her manner to you as a child; but it was the same with us all, or nearly so. She never knew how to be pleasant to children. But you are now of an age to be treated better; I think she is"All dialog and it does contain the word “love” in a lot of them. But without looking at other text, it’s hard to say if that is a distinguishing characteristic of this text. So let’s now look at the unpopular items.

Unpopular Text

In terms of the anti-hubs, we have a large number of those, so let’s sample 6 at random:

unpopular_indices <- which(k_occurrences == 1)

data_processed[sample(unpopular_indices, 6), c("book", "text")]# A tibble: 6 × 2

book text

<fct> <chr>

1 Emma "a letter, among the thousands that are constantly passing about the kingdom, is even carried wrong--and not one in a million, I supp…

2 Northanger Abbey "Catherine heard neither the particulars nor the result. Her companion's discourse now sunk from its hitherto animated pitch to nothi…

3 Mansfield Park "whose distress she thought of most. Julia's elopement could affect her comparatively but little; she was amazed and shocked; but it …

4 Persuasion "tried, more fixed in a knowledge of each other's character, truth, and attachment; more equal to act, more justified in acting. And…

5 Sense & Sensibility "but not on picturesque principles. I do not like crooked, twisted, blasted trees. I admire them much more if they are tall, straig…

6 Sense & Sensibility "and though a sigh sometimes escaped her, it never passed away without the atonement of a smile. After dinner she would try her pian…And here’s the full text of a randomly selected item:

data_processed[sample(unpopular_indices, 1),]$text[1] "unwelcome, most ill-timed, most appalling! Mr. Yates might consider it only as a vexatious interruption for the evening, and Mr. Rushworth might imagine it a blessing; but every other heart was sinking under some degree of self-condemnation or undefined alarm, every other heart was suggesting, \"What will become of us? what is to be done now?\" It was a terrible pause; and terrible to every ear were the corroborating sounds of opening doors and passing footsteps. Julia was the first to move and speak again. Jealousy and bitterness had been suspended: selfishness was lost in the common cause; but at the"There’s definitely a different flavor to the text of the anti-hubs we see here compared to the hubs, but this is only a small fraction of the anti-hubs. At least it isn’t just pulling out passages from Northanger Abbey.

Popular and Unpopular Words

It’s not entirely obvious what the difference is between the popular and unpopular texts. Maybe we can look at the average tf-idf value of the words in the most and least popular texts? To check this makes any sense at all, let’s just see what the most popular words in Pride & Prejudice are with this method:

pap <- tfidf_sp[data_processed$book == "Pride & Prejudice", ]

mean_pap <- colMeans(pap)

names(mean_pap) <- colnames(tfidf)

mean_pap[mean_pap > 0] |>

sort(decreasing = TRUE) |>

head(10)elizabeth darcy bennet bingley jane will said wickham collins lydia

0.04253865 0.03290232 0.02795931 0.02545364 0.01991761 0.01847970 0.01713893 0.01687501 0.01687119 0.01438015 That actually correponds ok with results from the

tidytext vignette: it’s mainly character names (and, er,

'said').

If we apply this to the dataset as a whole:

mean_tfidf <- colMeans(tfidf_sp)

names(mean_tfidf) <- colnames(tfidf)

mean_tfidf[mean_tfidf > 0] |>

sort(decreasing = TRUE) |>

head(10) will mrs said must miss much one think know never

0.01630534 0.01513324 0.01446493 0.01388111 0.01355313 0.01307697 0.01266730 0.01200490 0.01169455 0.01152472Now we have more generic words, although said is still

there. Way to go, said.

What do the popular words look like (and is said in

there too?):

mean_popular_tfidf <- colMeans(tfidf_sp[popular_indices, ])

names(mean_popular_tfidf) <- colnames(tfidf)

mean_popular_tfidf[mean_popular_tfidf > 0] %>%

sort(decreasing = TRUE) %>%

head(10) love quite well feel think like shall sure nothing yes

0.08188918 0.07007464 0.06825873 0.06808318 0.06540969 0.06223084 0.06055058 0.05710714 0.05624428 0.05375587 There’s love right at the top. No said to

be seen, and not a lot of overlap with the average words.

Onto the unpopular text.

mean_unpopular_tfidf <- colMeans(tfidf_sp[unpopular_indices, ])

names(mean_unpopular_tfidf) <- colnames(tfidf)

mean_unpopular_tfidf[mean_unpopular_tfidf > 0] |>

sort(decreasing = TRUE) |>

head(10) every much mind might must harriet without one long first

0.014918830 0.011596126 0.011479893 0.011270905 0.011188771 0.010718795 0.010047623 0.009764715 0.009650010 0.009499682 There is a bit more overlap with the average words here, but what was it Tolstoy said about unhappy families? I wouldn’t necessarily expect a theme to emerge from chunks of text which have nothing in common with anything else.

So there you have scientific proof that if you want to sound like Jane Austen, write about “love”. “think” and “feel”. If you don’t want to sound like classic Jane Austen, sprinkle in an “every” and a “long”. Also “Harriet”. Good luck.

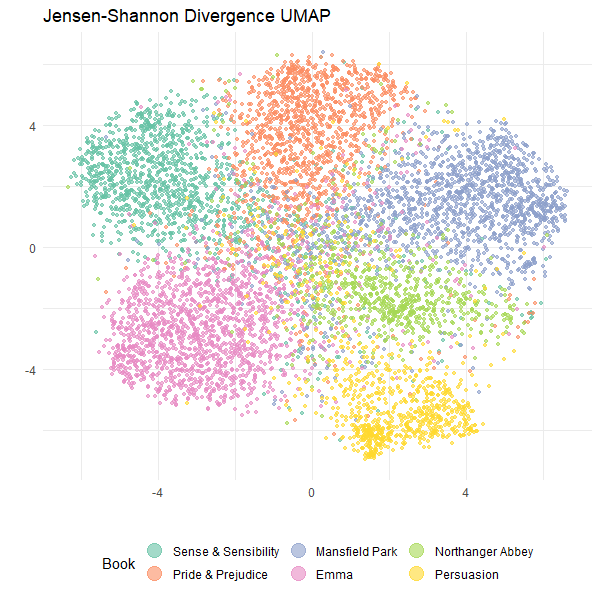

UMAP

We can also visualize the neighbor graph by carrying out

dimensionality reduction using UMAP via the uwot package.

This will attempt place nearest neighbors close together in a 2D scatter

plot.

uwotdoesn’t need any more input information than the

k-nearest neighbor graph, which you pass to the nn_method

parameter. This also requires explicitly setting the usual data input

parameter X to NULL. I am also setting the

density scaling to 0.5, which attempts to re-add some of

the relative density of any clusters in the data back into the embedding

using the LEOPOLD

approximation to densMAP.

UMAP uses a random number generator as part of its contrastive learning style optimization, but I am purposely not setting a random seed so that you will get different results from me. This is a way to avoid over-interpreting the layout of the clusters. I recommend running the algorithm a few times and seeing what changes.

js_umap <-

umap(

X = NULL,

nn_method = tfidfl1_js_bf,

n_sgd_threads = 6,

n_epochs = 1000,

batch = TRUE,

init_sdev = "range",

dens_scale = 0.5,

verbose = TRUE

)Plot

Let’s plot what we got:

ggplot(

data.frame(js_umap, Book = data_processed$book),

aes(x = X1, y = X2, color = Book)

) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.6, size = 1) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set2") +

theme_minimal() +

labs(

title = "Jensen-Shannon Divergence UMAP",

x = "",

y = "",

color = "Book"

) +

theme(legend.position = "bottom") +

guides(color = guide_legend(override.aes = list(size = 5)))

Hey, that looks pretty good! We can see that the texts from each book are mostly clustered together. The clusters for “Persuasion” and “Northanger Abbey” are smaller than the other books. In terms of the relative position of the clusters, you must take care not to over-interpret this. When I re-run UMAP multiple times the clusters do move about, but “Pride & Prejudice” and “Sense & Sensibility” usually end up together.

Neighbor Preservation

To get a more quantitative sense of how well this reduction has preserved the high-dimensional structure, we can calculate the nearest neighbors in the 2D space and compare them to the nearest neighbors in the high-dimensional space.

With only two dimensions, brute force search is very fast. UMAP uses

the Euclidean distance in the output embedding to match the

similarities in the input space, so we use

metric = "euclidean" rather than

"jensenshannon":

umap_nbrs <-

brute_force_knn(js_umap,

k = 15,

n_threads = 6,

metric = "euclidean"

)Now we can measure the overlap between the two neighbor graphs:

neighbor_overlap(umap_nbrs, tfidfl1_js_bf)0.1604303So on average 16% of the neighbor list was retained after embedding into 2D. Although this doesn’t sound like much, this actually pretty standard for UMAP (and maybe a bit better than normal). Your numbers are going to vary a bit from this, but hopefully not by much.